Stronger At The Broken Places

They interrupted the fight to go out to the party, because they’d promised, because they’d be missed, looked for, found and questioned. They stood together but spoke separately to separate friends, never to each other. He fetched her a new hot cider when it was time, because it was expected.

Eventually the night and the friends and the cider softened them, and they caught each other’s eye, and then stood a little closer, and brushed hands. Eventually there were smiles, and gentle words, and apologies.

They left the party to go home, holding hands, not at all from being tired.

Lacrimosa

What was it, that piece that Grandpa Knowles always played, the one I loved then hated then loved again when it was too late? He told me, several times, but I don’t remember the name; it’s lost somewhere amidst comic books and reruns and realizing girls smelled nice. If I knew more about music — anything about music, to be honest — I could at least narrow it down from the style. I’d know it if I heard it, I’d bet anything.

I wish I could ask him. But there’s a dust cover on Grandpa Knowles’ piano now, has been for years.

Falling Action

His cup was one of those oversized ones, big as a bowl of soup. “How much time have you got?”

She looked at her phone, because she’d stopped wearing a watch ages ago. “Half an hour. Forty minutes if I take a cab instead of walking back.” Hers was a medium to-go with the cardboard band around it.

They used to meet for coffee twice a week, then it was three times a week. Then it was once a week, but it was in a hotel room. They were back to coffee, now, just coffee: less complicated. “I knocked off for the afternoon. Slow at work. Thinking of walking over to the park.”

“You should do that. You totally should.” Without me. She didn’t need to say it, he’d always been good at reading her. That had never been their problem.

“I think I will. How’s George?”

You don’t care how George is. “George is fine. Working less, which is nice. Less stress, more time with the kids.”

“That’s good.”

“They’re moving me up, though, so I get less, so, there you go.”

“Always the way it is.” He stirred, absent-mindedly.

She checked the time on her phone, again. “Ugh.”

Wobbler

“You OK?”

She waited before answering, still angry, still frightened, the rhythm of her pounding heart syncopating against a chorus of distant car alarms. “Yeah.”

“We should head for the stairs, there’s—”

“Fuck off.”

“Listen, I—”

“Head for the stairs, go on. Nobody’s stopping you.” There was dust settling on her tights; she brushed it violently off, then her shoulders, arms, shook it out of her hair.

He got out from under the table, stepped gingerly over broken glass to a suddenly open window, looked out, whistled. “The front of Hawley Hall fell off. Like, you can see into the rooms.”

“John, I don’t give a shit, get out. Get out. You don’t get to tell me that you want to break up and that you cheated on me and then act like nothing happened. I—”

“There was an earthquake, Ariana.”

“I don’t care.” She pushed back further under the table, until her back was against the wall. “Go.”

“You can’t stay in here. It’s not safe.”

“I want you to leave. Fucking go find Carrie or whatever the fuck her name is.” Outside, sirens were starting to sound. “Go. I hope Hawley Hall falls on the both of you.”

Absentee

“You said you’d… yes, I remember. Yes, no, I understand how hard it is to… It’s just that you promised him. He has the new rod and he’s been practicing casting, and he wouldn’t stop talking about it all month and then… Bob, I get it, but he’s ten. He’s ten. He hears his dad say ‘I’ll be there’ and then you’re not there and he’s disappointed. He’s more than disappointed, he’s heartbroken. He… yeah. Yeah. I’m sure it’s very important. I know how they are about those meetings but… Okay. I’ll tell him. Just, Bob? No more promising, okay?”

That One Last Time

“You’re going to drive cross country,” Shep’s father said, “all the way to California, in that?”

“It’s a good car, Dad, it—”

“It’s a piece of crap.” The old man brought the beer to his lips, sucked the froth from the top noisily, in a way that had bothered everyone around him for twenty years or more. “Break down before Mississippi, I’ll bet.”

“Maybe. But I’ll fix it and keep going.”

The old man shook his head. “Stupid.” He turned, went back into the house to where his football game was playing.

Shep left that night. The Panthers lost, 21-3.

Deep Reds

He found her, finally, in the Renaissance. She sat quietly, watching the paintings as if expecting them to change, to move, to speak, to peel themselves open and offer her transport into another time and world. He sat beside her, not too close, just out of the corner of her eye, so she would feel his presence but still ignore him if she chose.

Eventually, she reached out and held his hand. “I don’t like this one.”

“Why?” He knew it wouldn’t be about the painting, not really.

“The Queen isn’t happy. She’s pretending to be, but she isn’t, really.”

After The East Central Game

She met him where she was supposed to meet him, where she always met him: an illuminated island in a forest of darkness. “Did you get beer?”

“Only two.” He’d already almost finished one, and the odds were fair to good that they’d end up sharing the other. “Terry kept the rest.”

“Fuck Terry.” She took the second beer, the last beer, and twisted it open in the cinched-up edge of her sweatshirt, and took a long gulp. “If he’s gonna take four out of six he’s gotta pay half. I don’t care if he’s the only one with I.D.”

“What do you wanna d—”

“Make out.”

He turned red, looked around nervously. “Uh…”

“I mean, don’t you? If you don’t that’s okay, I guess.” She tilted the beer up again, killing all but a third of it. “I just figured, you know.”

“I mean… I do, it’s just, I didn’t think you’d be…”

“What? Horny?” She stared into space; her pupils had adjusted to the gazebo’s lights and everything around them was jet-black nothingness. “We’ve got a month of school left. Do you really want me to be all coy about it?”

He laughed. “I guess not.”

“Then c’mere.”

Mouthpiece

“What are you going to do now,” she sipped her coffee, trying to ignore the pigeons around her feet, trying to pretend there wasn’t a little too much of a chill in the air, trying to seem like it was a casual question, “now that you can’t play?”

He shrugged; he wouldn’t meet her eyes. It was as if he didn’t just not know the answer, but that he believed there wasn’t an answer.

“Can they fix your—”

“No.”

She stared at the tiny aperture in the coffee cup’s lid. “It doesn’t seem fair.”

He laughed. “Why would it be?”

That Magic Moment

Waning hours of daylight, last day there, we held hands and walked down to the lake; one more time amongst the frogs and crickets and fireflies, one more time with the creaky planks of the dock under our bare feet, one more time waiting for perfect darkness to fold over us, holding us immobile until our pupils adjusted.

“I love you so much more than when we got here.” She said it into the crook of my neck, muffled, content. “This has been perfect. Let’s come back next year. All right? Please?”

She doesn’t know I’ve bought the place, yet.

Retrieval

I can’t believe you, she said. I can’t believe you did this to me. To us.

It had been early evening, then, the sun low on the horizon surrounded by streaks of red and orange as if to frame her anger with a complementary background, the light glinting off her ring as it sailed from her hand out into the featureless water. Now, it was early morning, days later, almost a week; the rented yacht long gone, replaced by a dinghy with an outboard four-stroke motor.

I’m sorry, okay? I over-reacted. I should have trusted you. Her voice was chastened, humbled, pleading. What do we do?

He leapt from the boat into the water, no mask or tanks, head down and eyes open, trying to find that lost glint against the deep blue darkness.

It’s still down there… somewhere down there is my ring. She took his hand. Please, John?

Do You Still Feel The Pain

“Daniel?” She called down the hallway, then walked down it peering through doorways until she found him. “Daniel, I’ve made dinner. Do you want some?”

“I’m having fish.”

“Have you caught anything yet?”

“No but I will.”

It was rushed out, as if to head off any questioning of his eventual success. “Well, that’s fine, but maybe you could come eat something to tide you over until they start biting?”

“Don’t want to miss any. Don’t want to.”

“All right, suit yourself.” She paused. “Can I at least bring you a plate?”

He didn’t respond; he jiggled the rod and watched the disturbed water bounce around the bowl. She walked back to the kitchen, took his plate from the table, began spooning little garlic potatoes onto it, one by one, eventually moving on to the green beans. By the time she reached for the salad tongs, she was fighting tears.

Rhonda’s First Epiphone

“Legs like that, you oughta be a dancer,” he drawled, a leery grin pasted on his face. Of course he didn’t mean a ballet dancer or a ballroom dancer or any kind of dancer outside of the ‘gentlemen’s club’ out on State Route 4. He downed another shot of Jack straight from the bottle and fumbled with the guitar, trying and failing to find a chord he’d hazily stumbled across a half hour ago.

“Gee, thanks, mister.” Her momma had taught her to be polite, at least on the outside. She smiled and nodded and kept just out of grabbing range until he passed out on one of the motel beds, pants unbuckled but still on, trucker cap over his face.

It was a nice guitar, and he hadn’t earned it. He’d be mad, come looking for it, but he’d never find her; he’d never really looked at her face.

Sculpture Of The Italian Renaissance

“Are you ready?!” She whispered it, taking each of us by the hand, eyes twinkling and darting and flaring.

Brendan looked at me and I at him: one of us would marry her, years from now, and the other would be quietly, respectfully disappointed. I nodded, lying, aware that any moment could be the moment where she chooses, deep down, perhaps herself unaware that it had happened. Brendan nodded as well, perhaps for the same reasons.

We were politely asked to leave. The security guard wasn’t angry at all. He seemed entirely unsurprised to find the three of us tearing through the museum at top speed, and could not have been more bored with the speech he gave us about decorum and proper respect and this and that and go on, now, off with you.

Brendan blew him a kiss from the doorway. She’ll pick him, I just know it.

Ava

I only took one.

They said take half. Cut it with a paring knife, a sharp one, so that you don’t lose bits, put half under your tongue, put half in a baggie. I didn’t have a paring knife, who has a fucking paring knife? Your mom has a paring knife. I took it whole.

I didn’t want to deal with everybody else’s freakouts and bullshit revelations and unfortunate nudity. I took a walk. There was a path that goes along the fence and then down through the seawall to the beach. The evening sand was kind to my bare feet and the waves were politely hushed as they loitered near the shoreline.

I thought, I’ll watch the sunset. It’ll be pretty. That’ll be a good trip. But then the gulls were all over the beach, and then in my hair, and then in my head.

Just do half, motherfuckers.

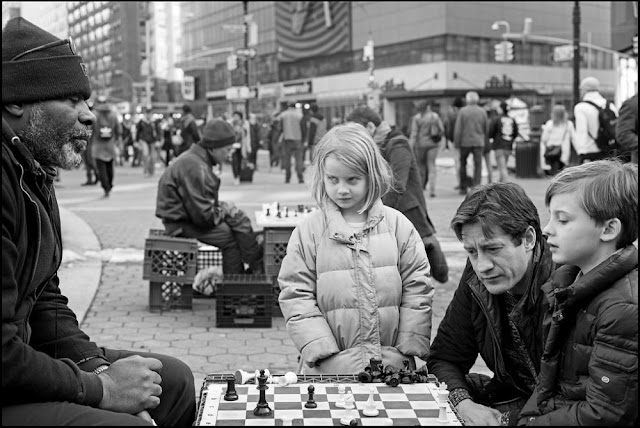

Rc2#

“It’s almost Milton time,” says Gracie, and she’s already pulling on her shoes and her coat and looking in vain for her mittens; Paul is watching cartoons, and seems unconcerned, and has to be coaxed away.

It costs $5 plus the four-block walk, but Daddy pays. Most of the others won’t play kids, but Milton will play anyone of any age once, calls it ‘fishing’; he plays Paul once a week, and usually wins. Usually.

“I didn’t play well as him, maybe ‘til I was twenty-five, maybe thirty. And I ain’t gettin’ no better. He’ll beat me often as not, he gets to driving age.”

Daddy asked Milton once if he’d like to come for dinner. Milton looked at him like he was crazy. Paul shakes Milton’s hand after every game, very grown-up, because that’s what you do when you’re part of that club and Paul is part of that club. Gracie watches the game, sometimes, especially if Paul is winning, but is sometimes distracted away by pigeons or dog-walkers. Daddy watches the game always.

On the walk back, Paul will talk about the game, if it’s close; if he wins, it’s a breathless torrent of excited recapitulation. If he loses badly, he doesn’t talk about it until bed-time, and then only in low, humble whispers from the under safety of his comforter, as Daddy listens and nods and pats him on the shoulder.

Sunday afternoons, spring, through summer and fall, and to the first snowfall at least, maybe longer.

FDIC Insured

She’s the kind of professional thief you hire to break into your place to see if it’s possible to break into your place. She’s trustworthy to exactly the extent that she keeps her promises to the letter, and no further. She comes highly recommended by all the right people.

“I paid a lot of money for this vault. I’m told it’s impregnable.”

She smiled. “Anything that can be entered legitimately can be entered criminally.”

“How?”

“You have my quote in front of you.”

We paid. She smiled, walked out, and we never saw her again. A week went by, and we started making phone calls: where is she, why no contact, how can we get our money back?

It wasn’t until I opened my personal lockbox — virtually a vault-within-a-vault — and found the note she’d left, that I realized she’d been and gone.

Needs work, it said. There weren’t any details.

Returned Unopened

My Dear Harry,

I hope this letter finds you well. I have heard from Etheline — her young man is in Cairo with Alexander’s staff — that the fighting around Tobruk is heavy. Please don’t take unnecessary risks and remember that you have people waiting for you at home, chief among them Stewart who is certain that you shall marry me and thus finally provide the big brother he clearly deserves instead of merely the terribly disappointing sister who can’t even manage to throw a ball properly.

I have been moved up to shift lead at the plant, so I am even busier than before. Your mother brings me cakes at least once a week, and Penny comes across from the shop to have lunch most days unless they are too busy. She is becoming a good friend and I cannot wait to have her for a sister.

Please do tell me if there is anything more I can send. I am knitting more heavy socks and a smart blue cap which is almost done. Penny has some things for you too, and Stewart has with great gravitas — and, I think, selflessness — donated some of his hard candy.

I must go as my break is over, so this short letter will have to do for today. I will sit under the crooked Alder at the bottom of the hill tomorrow and write you a longer one, so long as the air-raid sirens cooperate.

Love always and waiting patiently,

Your Annabelle.

Artist’s Model Needed

Phone numbers typed on little slips of paper torn from the bottom of flyers thumbtacked to bulletin boards have never once, in all my life, failed me.

Things I did not say to Gloria: “You have a grandma name, what’s that about?”; “You remind me of Katy Perry, especially in the chest.”; “Is this whole art class thing just a way to get people naked so you can get laid without going to frat parties?”; “Can I bring my boyfriend next time, this whole thing is weirding him out?”

She painted me four times over the course of two months. She didn’t take reference pictures and then paint from that. I sat for her, long afternoons bathed in light spilling in through the high-set studio windows. She introduced me to her teacher while I was wrapped in a sheet, which he affected not to notice.

After the third time, she took me for coffee. “I have to stop painting you. I’m attracted sexually and it’s distracting me from the work.”

We agreed that it was best to stop the sessions. We made small talk and finished our coffee and went our separate ways. She showed up at my dorm room five hours later and knocked on it and when I let her in, she kissed me without saying anything.

We dated for six months. She painted me one more time, after that night, but it wasn’t the same; she wasn’t painting me anymore, she was painting this version of me that she loved and fucked and argued and made up with.

I’ve shown my husband those paintings. The last one, the fourth one, is his favorite, I think because that’s the wife in his head. I can’t stand it, myself; I like the third one, because it’s all about unrealized longing.

See The World

I used to run away constantly. Like, constantly. Like, once a week. Usually my parents would find me within an hour, they knew all the places I would head for; I was a predictable kid, I guess. They’d check the park at the end of the street, the ice cream shop at the bottom of the hill, the big pink house where I thought a princess lived (it was a retired accountant. Once she let me in and made me tea and called my parents to come pick me up.)

Once I made it all the way down to the beach. That time I’d been missing for four hours, Mom had called the cops, it was a whole thing. Apparently I’d caught a city bus even though I had no money and was in bare feet and a tutu, although I don’t remember it. I even made the nightly news.