“We do it here.”

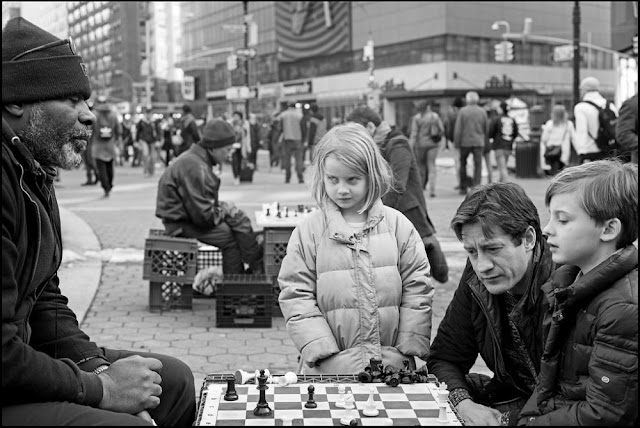

He stared at her, waiting for something to occur to him, something to say, a way to convince her to change her mind; nothing came. Eventually, he answered, “We can go on a little ways, maybe to—”

“No.” She already had her backpack off her shoulders and resting on the crumbled brick. “We do it here. You want all the forty-five ammo, right?”

He watched her dig out two boxes of bullets; he hadn’t taken his pack off yet. “Kit…”

“I should have all the nine millimeter,” she continued, placing the ammunition boxes on a brick and ignoring his lack of answer, “and the smaller knife. All the food we can divide equally.”

He shrugged off his backpack and sat down, waited.

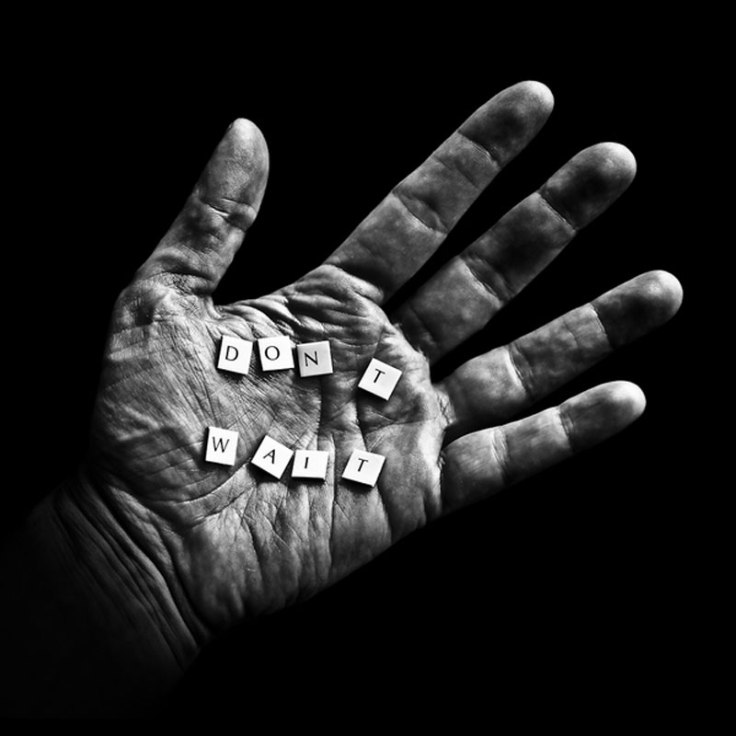

“Howard, we’re doing this. I’m sorry.” Kit shook her head, sighed. “No, I’m not sorry. We’re doing this here, now, while there’s still enough light left for us to get some distance between us before the sun goes down. And you’re not going to track me, you’re not going to play out some sort of fantasy where you follow me to keep me safe and leap out just in time to save the day. I don’t need that. I don’t want that. We’re done.”

He stared at the floor.

“We’re done. Do you understand? We’re—”

“Yeah.”

“Do you?”

“Yeah.” He wished away the panicky feeling roiling his stomach, the flush of heat around his ears, but they didn’t go. He breathed as normally as he could, an act of will. He fished a half-empty box of nine millimeter out of a side pocket. He managed, “You’re getting the short end on the ammo.”

“I don’t care. I’ll find more.” They exchanged boxes without their eyes meeting. “And the food? Matches?”

“You’ve already got half the matches. There were only the two books. And the food…” He peered into his backpack. “… I dunno. Take what you want.” He zipped it up, pushed it towards her with a shaky hand and then a foot.

“I won’t cheat you.” She said, as she started rummaging through his pack, as if he needed convincing.

“I trust you.”

She shook her head, made a sound of disgust that was a knife to the back of neck. “You shouldn’t trust anyone. There are terrible people out there—”

“That’s why you should stay with... why we should stay together. Just as partners, that’s fine, I don’t have a problem with that.”

“It’s done, Howard. I want you to walk away. I want you to walk away and not look back, because that’s what I’m going to do.” Kit finished stuffing cans into her bag, zipped it up, tossed it over her shoulder. “I really mean it. I don’t want to have to shoot you, Howard. I don’t want to; but I will.” She stepped through the breach in the wall and was gone.

She’ll do it, too. He waited, a long time, and then set out in the other direction.